Introduction

The Fossils

Paleoecology of the Crown Point Formation

Resolution of Recent Uncertainties Regarding the Fossil Display

Acknowledgments and Sources

On the south side of the Mall, between the grey cylinder of the Hirshhorn Museum and the crenellated brownstone of the Smithsonian Castle, stands a colorful brick structure known today as the Arts and Industries Building.

Shuttered for repairs, the building has long been emptied of exhibits. For many visitors, the building may be most memorable as an ornate backdrop to the adjacent children’s carousel. A curious passerby approaching its Mall entrance finds locked doors; a sign in the doors announces that the building is closed to the public. Stepping back, one can see engraved high on the wall above the entry arch the words, “National Museum” and the year “1879.”

The title “National Museum” seems surprising for a single building in a city seemingly full of national museums. A few yards away a Smithsonian kiosk provides an explanation.

The Arts & Industries Building is the nations’ first “National Museum” — the first Smithsonian structure built for the sole purpose of exhibiting the collection to the public. Constructed during 1879-1881, its design reflected several major currents of nineteenth century thought on museum design. Each element of the museum — structural and decorative – consciously embodied the goals of the architects, practical, aesthetic, and symbolic.

The lucky visitor who can enter the building by permission should therefore carefully examine its architecture – including the architects’ choice of floor design and materials.

A closer look reveals a vast display of fossils:

The fossils include a broad sample of the members of a reef community dwelling in the Ordovician period, nearly 480 million years ago.

The stone, a limestone commercially known as “Champlain Black Marble” (and sometimes as “Radio Black Marble,” because of its use in Radio City Music Hall in New York City) was quarried from the Crown Point Formation of Isle La Motte in Vermont.

Although this stone is found elsewhere in the city (see Gallery 4), the vast scale of the display here is unique in the public areas of the city – even though access to the halls of the Arts & Industries Building is at the moment by special arrangement only.

The dominant fossil visible in the floor is also the most distinctive fossil of the Crown Point Formation: the gastropod Maclurites magnus:

Maclurites magnus is an extinct, snail-like marine gastropod. Maclurites grew to as much as six inches in diameter and probably fed on algae.

The fossils do not always appear in perfectly aligned cross-section. Here is another Maclurites, of quite different appearance, because the fossil is cut through at an oblique angle:

Other distinctive shells also appear:

The matching jaw-like shapes above appear to be a cross-section of the unhinged halves of a bivalve shell – either a brachiopod (see Gallery 5) or pelecypod (like a modern clam). The fossil above the bivalve appears to be an oblique cross-section of a Maclurites.

Again, precise identification is difficult. Both brachiopods and pelecypods were filter feeders with hinged shells; though superficially similar in appearance, their differences are discussed in Gallery 5.

The reef included plants as well, as this fossil shows:

This photograph shows fossilized algae – stromatolites, whose successive layers helped to build up the reef-like structures.

Alongside these recognizable fossils are a host of other fossils, broken and obscured, from the same reef-like marine communities. The fossils provide a window into a rich Ordovician ecosystem in what may have been the first reefs in the world known to host corals.

Paleoecology of the Crown Point Formation

Geologists studying the outcrops of this stone on Isle La Motte, chiefly on Goodsell Ridge, have reconstructed much of the ecology of these reefs. They illustrate why reefs recur throughout life history and why they host rich and diverse communities: their physical structures provide a wide range of ecological niches for different plants and animals.

The fossils in this limestone (cut from what is formally known as the “Crown Point Formation”) were deposited over several million years during the Ordovician period, nearly 480 million years ago. The location of the quarry, now the northernmost island in Lake Champlain, was then below the equator, at approximately the current latitude of the Madagascar. The environment was a warm, shallow sea, on a platform slightly to the east of the continental land mass of Laurentia, which ultimately provided the continental core of what is now North America. The reefs lay at the western margin of the Iapetus Ocean – one of several predecessors to the current Atlantic Ocean.

The reefs that became the Crown Point Formation may more properly be termed “bioherms” or just “mounds” and were built up by lengthy successions of living communities growing, dying and leaving their remains. In these reefs, the principal “framebuilders” were bryozoa (“moss animals,” discussed in Gallery 6), stromatoporoids (filter-feeding, sponge-like creatures also informally termed “cabbageheads”) and stromatolites (layers of calcareous algae and cyanobacteria).

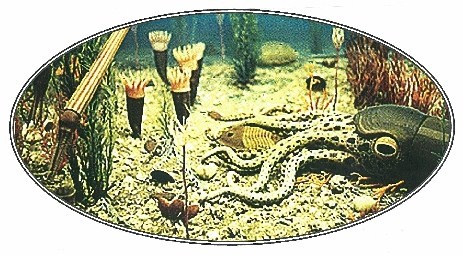

Once the reefs built up above the sea floor, they housed a rich and diverse marine community. Members included the gastropods (like Maclurites), echinoderms (including crinoids, see Gallery 9), brachiopods (seeGallery 5), sponges, trilobites and nautiloids (see Gallery 4). As Prof. Mehrtens of the University of Vermont has put it, these creatures were “the usual cast of characters in the Middle Ordovician seas.” Unlike modern reefs, which are dominated by carnivorous coelenterates feeding on floating or swimming organisms, the Crown Point reefs were dominated by suspension feeders (bryozoans, bivalves, sponges and crinoids). Trilobites and nautiloids were likely the only large carnivores. Below is a visualization of Crown Point community from the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts:

You can also view a recreated Ordovician seafloor community by viewing the diorama in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

The fossils of the Crown Point reefs show a clear succession of species. The stromatoporoids formed the pioneer community. Their built-up remains provided a favorable base for the later-arriving sponges, corals and algae. As in modern reefs, the fossil remains of these reefs show evidence of competition among different organisms for food and space. Some species prospered in shallower than in deeper waters within the reef areas, and vice versa.

While they were being formed in the Ordovician sea, the reefs followed a roughly north-south orientation, parallel to the “paleoshore” the neighboring land mass of Laurentia. The fossilized reef remains include channels that, in places, resemble in form the “spur and groove” structures in modern reefs which provide conduits for water to move from the open ocean to the lagoon behind the reef. Unlike modern reefs, in which these channels are typically formed during the reef’s construction, channels in the Crown Point reefs appear to have been cut by erosional action of incoming and outflowing wave surges and currents. In some places,Maclurites shells appear to have been piled as a result of paleocurrents. The multiple Maclurites shells shown in the first fossil photo in this Gallery may possibly be from one such pile.

The Smithsonian Institution’s collections were originally housed in the Smithsonian Castle, which combined exhibition with various other roles such as research and publication. Crowding became more severe over time. By the mid-1870s, the Smithsonian’s National Museum collection had outgrown its first home, particularly following the vast accession of material from the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition — sixty boxcars’ worth.

In response, the government planned a new “National Museum” whose principal purpose would be to display exhibitions – the first such building in the U.S. The basic plan of the new museum was drawn up by Montgomery Meigs, the military engineer who built the Washington aqueduct, the dome of the Capital, and other major public works in the District. In addition, the Smithsonian chose design modifications submitted by architect Adolf Cluss and his partner. Cluss was a native of German and was well versed in the principal 19th century European theories of museum design. European concepts focused on regularity and structural integrity intended to permit “the ideal relationship of objects and the ideal flow of visitors and light,” as Dr. Cynthia Field has noted in an article about Cluss.

The resulting structure appears highly ornate to viewers of the early 21st century. The builders’ principal goal, however, was thoroughly practical and in many respects very modern. The building incorporates many utilitarian features: the skillful use of indirect natural light through windows that also permitted air circulation; a successful effort to maximize floor space for exhibits; and the employment of “fireproof” construction of brick, iron and stone. Similarly, the floors’ slate borders and black white and red marble squares, as well as encaustic tiles in selected transitional areas, were decorative yet followed the functional goal of resisting wear.

Despite its fundamentally practical nature, the design also emphasized important decorative and symbolic elements. Careful thought went into the Museum’s ornamental features. Note the consciously flat and geometric floral designs in the interior walls, which embody the design concepts of prominent design reformers. Their colors combination (yellow and lilac) reflect a color combination advocated by Goethe to produce a harmonious and gladdening effect. .

The building’s choice of red brick facing reflected a conscious step toward modernity, yet at the same time incorporated decorative and symbolic features. The patterns of colored bricks help the viewer distinguish between load-bearing and “curtain walls,” whose interwoven glazed bricks suggest primitive weaving.

On the roof, high over the Mall entrance is an allegorical sculpture entitled, “Columbia Protecting Science and Industry.”

The architects therefore extensively used decorative appearances to convey the purpose of the museum and its structural elements. It seems unlikely that the architects would have chosen black flooring squares without carefully considering the presence of hundreds of vividly visible fossils. The Champlain Black Marble was a well-known stone in the late nineteenth century, but other durable, black building stones or tiles could have been used. It is difficult to conclude, that the stone was chosen above without conscious attention to the fact that it displayed the fossils of long-extinct creatures, on the floor of the country’s National Museum, whose earliest exhibits included geology.

Research to date does not reveal why the architects chose Champlain Black Marble, but it is very plausible that Adolf Cluss sought to display fossils in the fabric of the building. The geology exhibits long ago moved to the newer Museum of Natural History, but the flooring of the National Museum remains a rich contribution to the displays of paleontology in the city’s buildings.

An Uncertain Future for the Museum’s Fossil Display

Hundreds of miles separate the flooring stones of the Arts & Industries Building from the surface exposure of the Crown Point Formation at Goodsell Ridge on Isle La Motte. By a curious coincidence, however, both sites have both recently shared an uncertain future.

The threats to both appear to have been happily resolved for now. The Crown Point Formation and its fossils on Goodsell Ridge can be accessed by the public and by scientists, who may observe evidence of the reef formations in their natural state. In recent years, geologists and preservationists have feared that nearby active quarry operations could be expanded to consume the entire ridge, for building stones or even for road fill. Quarry operators might also have chosen to end access to the surface fossils. Fossil thieves and vandals also sometimes gained access to the unguarded exposures, destroying and removing prominent fossils. Happily, a successful effort to preserve the Goodsell Ridge exposures came to fruition in 2005. The land was successfully purchased to ensure that the outcrops are preserved for public efforts. Preservationists continue to seek to enhance and extend that important step, by purchasing an old farmhouse to serve as an indoor research center and museum. The effort is supported by the Lake Champlain Land Trust, and inquiries can be made at http://wwwlclt.org/GoodsellUpdate.htm.

The flooring of the Arts & Industries building recently also faced a potential threat. The building’s role in the Smithsonian system was in a state of limbo during the first decade of the century. Currently the building houses no exhibits and closed in part due to lengthy roof repairs. The National Trust for Historic Preservation added the Museum to its 2006 list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. (http://www.nationaltrust.org/11most/list.asp?i=181) and states that:

“The Arts and Industries Building suffers from neglect, a deteriorating roof, and other infrastructure problems. There is no clearly defined plan for its future use. Until that plan is developed and implemented, the Arts and Industries Building — a structure that was once dedicated to showcasing the nation’s historical treasures and is a historical and architectural treasure in its own right — languishes in an underutilized and deteriorating state.”

The original flooring stones, beautiful and rich in architectural and geological meaning, are also worn and damaged in many places. Some have feared that when the next use were found, the Champlain Black Marble flooring might be replaced with newer flooring. As of 2007, the Smithsonian had explored partnering with a private entity in the use of the facility for non-traditional purposes, including potentially, “a combination of stores, commercial offices, and exhibition and conference space.” Fortunately, in 2008 the Smithsonian decided to end the partnering effort and to restore the building’s appearance, to the extent feasible, to that of the early 20th century. By late 2009 work had begun, although funding for the full restoration project had not been allocated. The Smithsonian plans to restore the flooring that is not damaged beyond the possibility of repair, thus preserving part of Adolph Cluss’ unique building design as a grand exhibit in D.C.’s Accidental Museum of paleontology.

Acknowledgments and Sources[1]

Special thanks to:

Dr. Cynthia Field, former Chairperson, Architectural History and Historic Preservation, Smithsonian Institution, for her generosity in sharing information, suggestions and in providing access to the Museum.

and

Dr. Laurence R. Becker, State Geologist and Director, Vermont Geological Survey, for providing publications and fossil identification.; and Prof. Charlotte Mehrtens, of the University of Vermont, who identified the fossils in the pictures above.

About reef characteristics, paleoecology and early Ordovician geography and conditions:

“Paleoecology of Chazy Reef Mounds,” Neige (1972) at pp. 443-471;

“Chazy Reef Field Trip Isle La Motte, Vt.” Dr. Charlotte Mehrtens, for the Vermont Geological Society, University of Vermont, August 1998.

Another recent article on the paleoecology of the Chazy reefs appeared in the Smithsonian Magazine, “Paleozoic Vermont,” although it was not consulted for the discussion above (http://www.smithsonianmagazine.com/issues/2007/january/phenom.php).

Information about the Museum: The description of the architectural basis for the design of the building is drawn largely from the detailed and interesting piece, “Cluss’s Masterwork: the National Museum Building,” by Dr. Cynthia Field, published in Adolf Cluss, Architect; From Germany to America, by Alan Lessoff, Ed. (2005). Washington Post article, “African American Museum Poses a Siting Dilemma,” by Petula Dvorak, November 17, 2005, p. B 1. See also, “Arts and Industries Building (National Museum Building)” in Buildings of the Smithsonian, http://www.150.si.edu/sibuild/arts.htm. The National Trust for Historic Preservation’s account of the building’s state used in its America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places is found athttp://www.nationaltrust.org/11most/list.asp?i=181. Private use was discussed, in “Smithsonian Seeks Partner to Save Mall Landmark,” The Washington Post, May 9, 2007, page C-1.

About the formation, other architectural uses of the stone, and preservation efforts. “Saving Goodsell Ridge by Creating an Outdoor Museum and Fossil Preserve on Isle LaMotte, Vermont,” by The Isle La Motte Reef Preservation Trust & The Lake Champlain Land Trust (undated, but apparently published circa 2003).

[1] Where this website cites specific internet page addresses, they are typically the addresses used by the author in researching and writing this discussion – a process taking several years. Unfortunately, in the meantime a number of the specific addresses have changed, and will continue to change, rendering some of these addresses ineffective as links. Readers should be able to find the material by searching for the proper name of the cited article or material on a search engine.