How the Brachiopods Came to 23rd and S St., N.W.

Introduction

Not far from D.C.’s busy and often loud Dupont Circle neighborhood, a change of pace is readily at hand. Walk westward on P, Q or R St. to 22nd St., and turn right. Proceed north on 22nd St. Just past Decatur Place, you will arrive at Washington’s own “Spanish Steps.”

At the top of the steps, across S St., a city park stretches to the west. Turn left and follow the park to its end, westward along 23rd St. At the corner, by a steep retaining slope, you can take a seat on the low concrete wall.

(intersection of 23rd and S St., N.W., looking east from the 2300 block of S St.)

This neighborhood is known as Sheridan Kalorama. Nearby stand grand houses constructed early in the 20thCentury, now used as embassies, diplomatic residences and private homes. The neighborhood is generally quiet – though interrupted sometimes by the sound of children at the playground directly above.

The neighboring structures and even the current contours of the landscape are only the most recent face of the land. Prior to European settlement, Native Americans camped on this same slope, when it stood as a wooded rise above Rock Creek. In colonial times a manor stood a few feet away, which in the Federal era became home to a noted scholar and diplomat of the early Republic. Urban development reached the neighborhood late in the nineteenth century, when street grading changed the very shape of the landscape. Land for the park itself was deeded to the city after World War I in memory of deceased pet, after escaping possible development as the grounds for the French and then German embassies. During the 20th Century, the park was graded and leveled to create level playing areas high above 23rd St. After World War II facilities were developed on the park land, which were renovated by 1980, when the steep slopes of the park at the corners of 23rd St. and S St. and 23rd St. and Bancroft Place were reinforced with a pattern of large, irregular stones cemented together, with gaps to permit some vegetation. Further renovations and landscaping in 2004 brought a new look to the park, but no change to the embankments on 23rd St.

Turn toward the stones armoring the hillside and take a closer look.

The stones do not appear quite so ordinary. They contain hundreds of white and grey shapes, many of which are shell-like in appearance:

They are brachiopod fossils, which superficially resemble the clams and mussels one finds in beaches today. Brachiopods were filter-feeding bottom dwellers that thrived in seas throughout the Paleozoic and still survive today, though in vastly reduced numbers. Although there appear to be rocks from more than one geologic formation, it appears that many of the fossils are from the early Devonian period, slightly less than 400 years ago.

About the Fossils

Age and identity of the formation

The District of Columbia does not appear to retain records of the origin of these stones, and there is as yet no definitive identification of the age and geological formation from which the fossils were quarried. In addition, some of the rocks may have been mixed together from different formations during the process of quarrying and sorting the stone. However, it appears likely that the predominant rocks – those with extensive brachiopod molds — are Appalachian in origin, from the Oriskany Formation, created by sediments deposited in the early Devonian period, slightly less than 400 million years ago. The Oriskany Sandstone formed along the southeastern margin of a land mass, Laurentia, which later formed the core of the current North American continent. To the southwest lay a sea separating Laurentia from other land masses – one of several precursors to today’s Atlantic ocean. The resulting sandstone may be seen in outcrops visible along a line stretching from Ontario, through New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee.

Sandstone as a medium for fossil formation

The Mitchell Park fossils are preserved in sandstone. They are among the few D.C. sandstone fossils yet identified for inclusion in this website. Overwhelmingly, other identified fossils discussed here are found in limestone – typically deposited in a shallow sea or in-shore area of a larger body of water as the result of accumulating calcium-rich detritus left by the remains of animals and plants. In contrast, sandstone is commonly found in former river deltas or beach environments. Inland rocks weathered and supplied runoff rich in grains of quartz, a silica rich mineral, which accumulated much as it does today. At the margin of seas, such inshore environments often hosted a rich variety of marine sea life, but as a general rule such high-energy environments (due to waves, currents, shifting sands) cause sandstone formations to retain in far fewer fossils than limestone.

However, this sandstone has a wealth of shell fossils. The brachiopods of the Oriskany Formation were first buried in sand. Over time, overlying deposits of sediments compressed the sand, and calcium-rich liquid cemented the quartz grains together, around the shells. Eventually, the original shells were dissolved, leaving the detailed molds visible in the stones today.

Types of brachiopods

A number of different types of brachiopods exist in the hillside, but identification of specific species or even genera is not yet available. The following photographs contain brachiopods that superficially resemble some of the better known fossils of the Oriskany Formation, but we await authoritative identification:

About Brachiopods

How to distinguish brachiopods from clams and their relatives

Brachiopods superficially resemble pelecypods (clams, mussels, etc.), their common modern counterparts in shallow marine waters. Both brachiopods and pelecypods secret two hard shells, or valves, as a form of armor to protect their soft inner organs. Both join the valves at one end with a single hinge. Both typically display “bilateral symmetry” – bodies that have two halves that form mirror images. The difference lies in where the line is drawn between the identical halves of the organism. The key in identifying brachiopods is explained with illustrations in a work of the Pennsylvania geological survey:

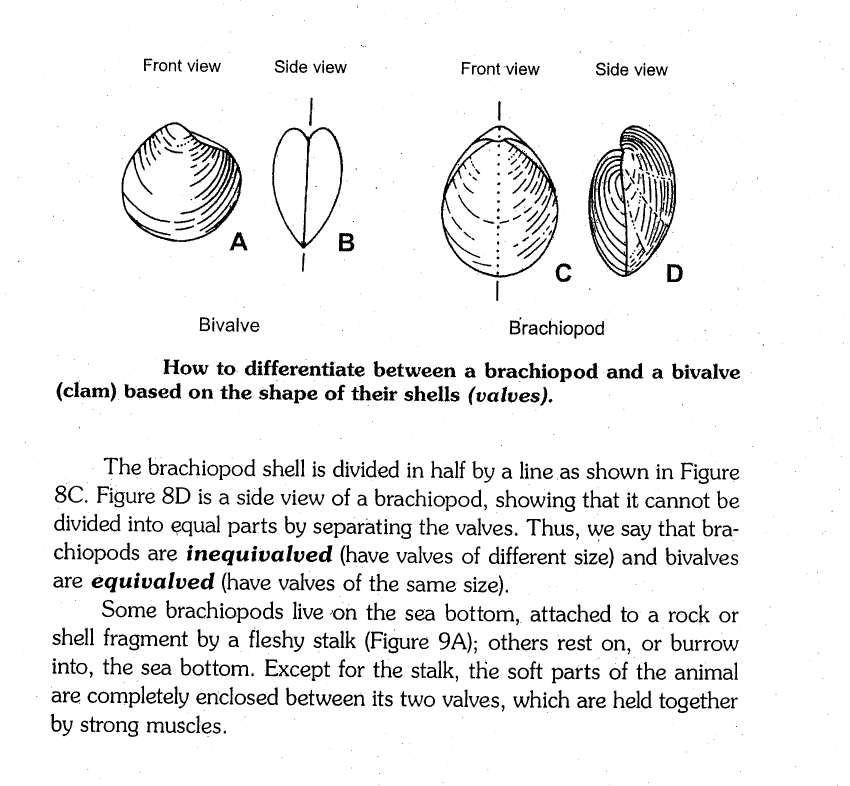

Perhaps the easiest way to tell a bivalve from a brachiopod is to divide them into two equal parts. Figure 8A shows the front view of a bivalve shell; no line can be drawn on it that will divide it into two equal parts. However, in Figure 8B, a side view, the bivalve is separable into two equal valves, hence the name “bivalve.”

Figure 8. How to differentiate between a brachiopod and a bivalve

(clam) based on the shape of their shells (valves).

The brachiopod shell is divided in half by a line as shown in Figure 8C. Figure 8D is a side view of a brachiopod, showing that it cannot be divided into equal parts by separating the valves. Thus, we say that brachiopods are inequivalved (have valves of different size) and bivalves are equivalved (have valves of the same size).

From Common Fossils of Pennsylvania, E.S. No. 2, Pa. D.C.N.R., the Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey, at pp. 10-11.

Internal Structures

Within the brachiopod’s hard valves, muscles run through its body to permit the opening and closing of the shells. The brachiopod also has a “lophophore,” an organ to strain and collect organic bits of matter as food, as well as a digestive tract and other internal organs. Each brachiopod grows a mantle to cover the organs and provide channels for the circulation of its watery blood, and often a pedicle to attach the shell to a surface – to a rock or other shell (although some rested on or burrowed in the sea bottom. The name “brachiopod,” from the Greek words “arm” and “foot,” stem from an early misunderstanding of the functions of this organ; but the name remains.

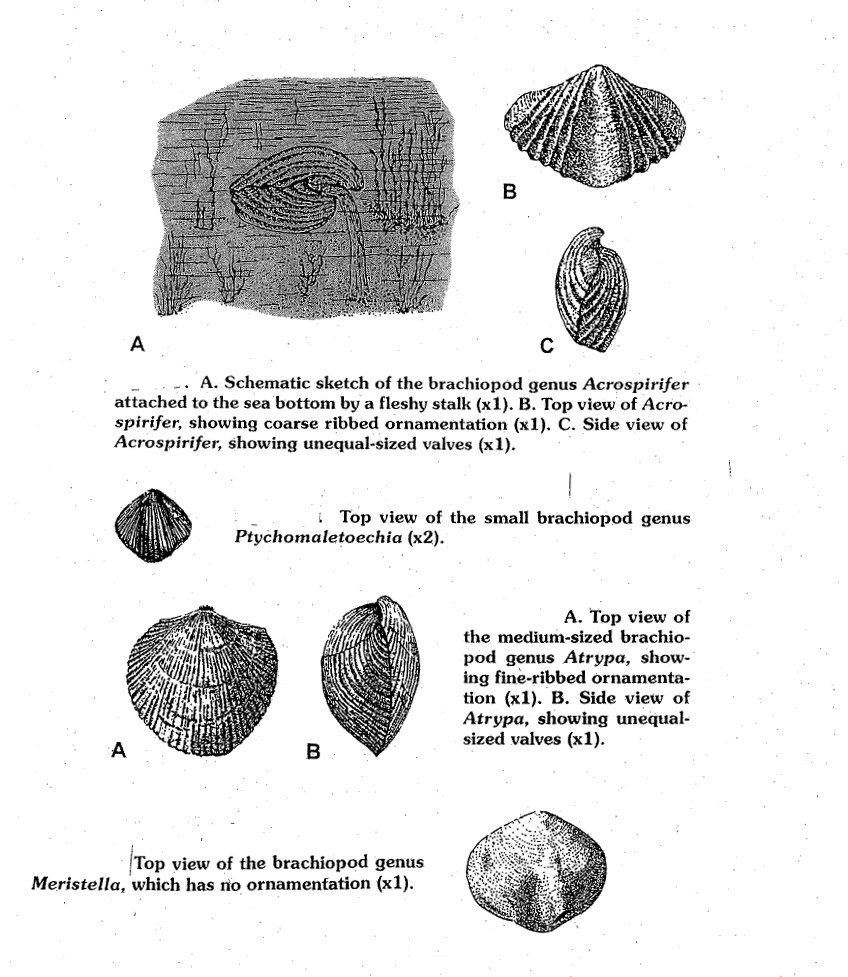

Examples of common brachiopod types as they would have appeared are shown below, also from the Pennsylania DNR E.S. No. 2:

Used courtesy of the Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey, Pa. D.N.R.

Close studies of fossil brachiopods, with the aid of magnified images, allow geologists to learn about some details about the individual brachiopod’s lives. The fossils reveal growth lines and surface markings showing the age of the brachiopods upon death, and even evidence of injuries. It appears that Paleozoic brachiopods, like their modern counterparts, were hardy, often living in turbulent environments, as well as in quiet tidal pools. As is so often the case in the study of fossils, researchers have benefited from observing the internal organs and life habits of modern day brachiopods to better understand those of their extinct relatives.

How the Brachiopods Came to 23rd and S St., N.W.

Before the arrival of European settlers, the future location of 23rd and S St., N.W. was on a descending wooded ridge overlooking Rock Creek valley to the west and south. To the southeast, the land shelved down to the Potomac in what is now the West End of the city. Archeological evidence shows an American Indian presence on the Mitchell Park site, including soapstone flakes and the remains of tool making.

In 1663, the park was within a royal land grant called “the Widow’s Mite,” and changed hands several times. In 1750, a colonial manor was built at the intersection of 23rd and S St., by Anthony Holmead, who owned a nearby paper mill on Rock Creek. Ownership of the manor passed through several hands. On May 3, 1802, Thomas Jefferson wrote to Joel Barlow, urging him to move to the new national capital in order to write a history of the young nation, noting as a postscript:

P.S. There is a most lovely seat adjoining this city, on a high hill, commanding a view of the Potomac, now for sale. A superb house, gardens, etc., with thirty or forty acres of ground. It will be sold under circumstances of distress, and will probably go for half of what it has cost. It was built by Gustavus Scott, who is dead bankrupt…

Five years later, Barlow purchased it, renaming the estate “Kalorama” (Greek for “fine view”), and enlarging it with the design assistance of noted early American architect Benjamin Latrobe. An early 19th Century watercolor, “Kalorama” by Charles Codman, is wonderfully suggestive of the setting, although it appears to take considerable liberties with the geography:

(Image is courtesy of the Diplomatic Reception Rooms, US Department of State, Washington, DC)

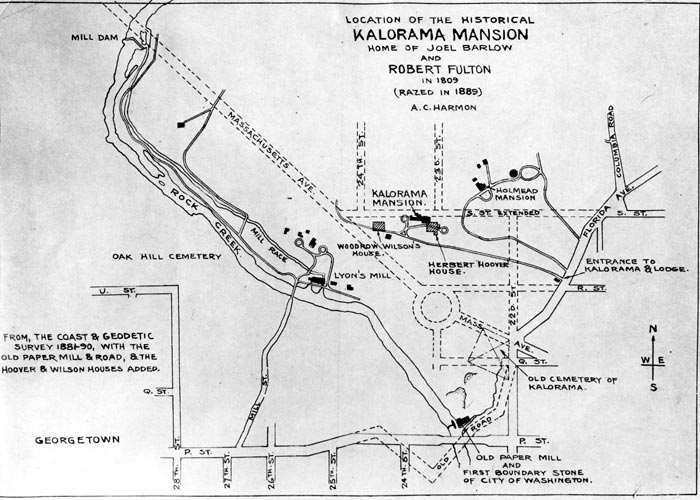

The location of the Kalorama mansion and the modern streets can be seen in the map below, which shows the modern intersection of 23rd and S St. to be a few yards to the northeast of the manor:

(With permission of the D.C. Historical Society, “Location of the Historical Kalorama Mansion Home of Joel Barlow and Robert Fulton in 1809, razed in 1889,” by A.C. Harmon)

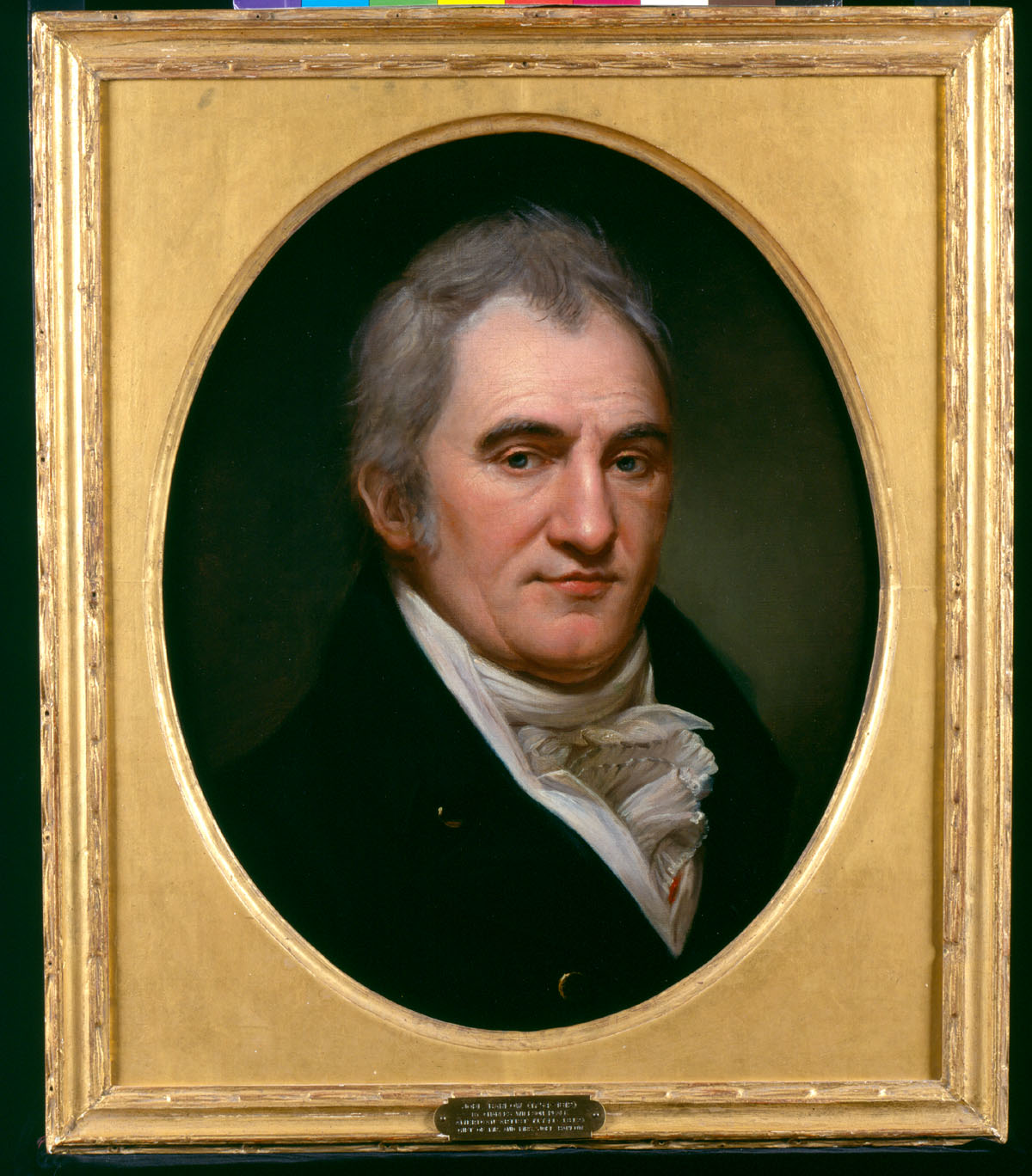

Joel Barlow was a Revolutionary War chaplain, diplomat, writer and part of a circle of very prominent friends in the new Republic. Barlow hosted Thomas Jefferson, among others and negotiated the first American treaty with the Barbary Pirates, freeing captive American sailors. The inventor Robert Fulton virtually became a member of Barlow’s family, and some sources report that Barlow dammed up a pool in Rock Creek below the manor to permit a trial run of a model prototype of Robert Fulton’s steam ship. A portrait of Barlow by Charles Willson Peale (1807) appears below.

(Image is courtesy of the Diplomatic Reception Rooms, US Department of State, Washington, DC)

Barlow died in Russia on a diplomatic mission to Napoleon, but the Kalorama mansion survived under different owners and until the late 1800s.

The manor was torn down in 1888 as urban development came to the area around the Widow’s Mite. At that time, the city was spilling out past the original city limit at nearby Florida Ave. (then, “Boundary St.”). In the late 1880s, the city planned subdivisions and installed graded streets. One newspaper account of 1887 noted major changes to the appearance of the land from the street grading around Kalorama as many old trees were uprooted and up to 18 feet of soil was removed in places.

Costly homes and mansions were erected around the site of the former manor between the 1890s and World War I. A large tract of land, including the land immediately north of S St. and east of 23rd St., however, was not immediately developed. For a time, it appeared that the French Embassy, and then the German Embassy, might be located on the remaining open area, but those plans came to nothing. After 1900 that land was sold to the Mitchell family. The Mitchells planned to build a home there, but never did so – although they did bury a beloved pet poodle on the lot. Eventually, the Mitchells left the land to the city for use as a park. The will of Elizabeth Paterson Mitchell, filed in 1917, provided:

To the City of Washington, D.C. I leave my lot on S Street to the memory of Morton Mitchell for a park. It was intended for our home, and our old dog, whose bones rest there, is not to be disturbed.

As denser residential construction occurred during the twentieth century, Mitchell Park became the sole public green space and token of the earlier Colonial open estate. The author has encountered little information regarding the park itself for most of the 20th Century – newspaper accounts do mention that tennis leagues played there and Halloween events occurred at the park. At some point, possibly after World War II, the west end of the park bordering 23rd St. was leveled, and a playground was installed at the Bancroft corner, and paved, fenced ball courts were installed at the S St. corner.

In 1980, the Park received a substantial renovation. City officials are not clear on the exact circumstances, but a newspaper reference and a longtime local resident point to this date for the installation of the stone armoring on the corners of 23rd and Bancroft and 23rd and S St. The architects called for a stone to be cemented on the hillside. The rocks used were almost certainly transported from quarries in the not-too-distant Appalachian region. The Oriskany sandstone is not typically used as a construction stone – it is mined and used for glass-making and similar industrial purposes. Discussions with the West Virginia Geological Survey suggest that it is quite possible that the stones used for Mitchell Park were originally removed from the ground as construction spoils – removed and set aside for later use. That theory would explain why they appear to have been jumbled together with other types of stones, and ultimately carted off for use as rip-rap to shore up a park slope.

Unintentionally, the city’s repair work installed a striking hillside display of organisms from the distant Paleozoic — an unlikely successor to the grounds of the grand colonial mansion that stood nearby and hosted the high society of the early Republic. Interestingly, one of Barlow’s friends, Thomas Jefferson, has been called American’s first paleontologist and was an early fossil-collector. He at least among the possible visitors to Barlow’s mansion might have found today’s nearby brachiopod display worth a close look.

Acknowledgments and Sources[1]

About the history of Sheridan Kalorama and Mitchell Park. “The History of Sheridan-Kalorama,” Traceries, Washington, D.C. 1988 (from the D.C. Public Library’s Washingtoniana Collection); “Kalorama: Country Estate to Washington Mayfair,” by Mary Mitchell, from Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 1971-1972; Brochure, Sheridan-Kalorama, Historic District, D.C. Office of Historic Preservation (2000); “A Tale of a Dig Dug and a Cover-Up Curbed,” The Washington Post, Thursday, October 23, 1980, by Anne Oman; “Neighbors of the Cosmos Club, The Story of Joel Barlow and His Kalorama,” by Richard B. Parker, at http://www.cosmos-club.org/web/journals/2001/parker.html , which also is the source for the quotation from Mr. Jefferson’s 1802 letter; personal communication, Richard B. Parker; personal communication, Holly Sukenik (approximate date of the installation of the stones). Mr. Jefferson’s considerable interest in fossils, though focused on mammalian remains, is discussed at http://www.acnatsci.org/museum/jefferson/index.html

About the identity of the fossils; Personal communications. Geologists at the Maryland Geological Survey, through the efforts of David Brezinski, reviewed pictures of the brachiopods but without a consensus as to age or location of origin. The West Virginia Geological Survey reviewed pictures as well, through the generous assistance of Dr. Don McDowell and Mr. Steve McClelland. Dr. Richard Diecchio, Professor of Geology at George Mason University, visited Mitchell Park and determined that the principal fossil-bearing rocks were sandstone; he suggested the Oriskany Formation as a likely source. Dr. McDowell subsequently indicated that the only likely brachiopod-bearing sandstones in the nearby Appalachian region were Cambrian sandstones and the Oriskany sandstone of the Devonian. The Cambrian sandstone is an unlikely source, in light of the large size of the fossils here. Therefore, it appears most likely that the fossils are from the Oriskany sandstone. Further input by geologists, particularly regarding the identity of the fossils, may be possible in the future.

About the Oriskany formation and the geology of Appalachia in the early Devonian. http://www.wvgs.wvnet.edu/www/geology/geolhist.htm; Geology of the Appalachian Valley in Virginia, Part I – Geologic Text and Illustrations, by Charles Butts (Va. Geological Survey Bulletin No. 52 (University of Virginia, 1940).

About brachiopods in general. The Fossil Book, A Record of Prehistoric Life, Carroll Lane Fenton and Mildred Adams Fenton (rev. ed., 1989) at 153-179. Common Fossils of Pennsylvania, E.S. No. 2, Pa. D.C.N.R., Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey, at pp. 10-11.

[1] Where this website cites specific internet page addresses, they are typically the addresses used by the author in researching and writing this discussion – a process taking several years. Unfortunately, in the meantime a number of the specific addresses have changed, and will continue to change, rendering some of these addresses ineffective as links. Readers should be able to find the material by searching for the proper name of the cited article or material on a search engine.